Blog Post

Are We Ready for Internet Voting?

Low voter turnout disappoints almost everyone who cares about democracy, but the patterns of voter participation clearly indicate a need for an alternative to the voting booth. The widespread use of the internet poses its potential for casting and counting ballots. Estimates from Internet World Stats cited 95 percent of the population of North America as internet users in 2018, a convenience that may enhance voter participation. However, concerns about trust issues and cybersecurity hamper acceptance of the concept.

Checking on the Viability of Internet Voting

Estonians have cast ballots online through i-voting for 10 years, and the country’s Head of State Electoral Office cited the success of e-tax and e-health at a seminar as relevant service deliveries. A cybersecurity expert stressed the importance of adopting best practices of “resilient risk management” and “active international and cross-agency cooperation” to ensure voter confidence in tallying votes. Estonians trust the i-voting system because of a belief in its cost-effectiveness and end-to-end verifiability.

A report from Fast Company, however, indicates a less satisfactory view of online voting. Jeremy Epstein, vice chair of the Association for Computing Machinery’s U.S. Technology Policy Council, agrees with tech and election experts that moving toward adopting internet voting constitutes a “giant security blunder.” He stated that a return to paper ballots represents the view of computer scientists “for a decade.” The BBC News cited the Estonian endorsement of i-voting, but Epstein states “that studies have still found plenty of risks with it.”

As the co-author of a report “Email and Internet Voting: The Overlooked Threat to Election Security,” by the R Street Institute, the National Election Defense Coalition and the Common Cause Education Fund, he notes the hazards of sending ballots by email. Hackers can intercept them and change information, and malware that he believes exists on as many as a third of all computers can alter voter responses. A meltdown that may result from such influences can create the “ultimate nightmare scenario.” One infected email that an election worker clicks may have the ability to affect a network of election offices at the county or state level. Further damage can result from loading configuration files through memory cards onto scanners and voting machines at election time. The concern, Epstein states, reveals the possibility of one email “swinging an election” while not even attracting attention.

Rejecting the Estonian Model

Epstein notes that every country except Estonia has “backed away” from online voting because of the risks that they see and the low quality of software that produces problems. He acknowledges that the system has a reduced risk with a connection to the Estonian ID card that makes it more reliable than the U. S., but he still considers it “really, really bad.” The technology exists for vulnerability scanners and web security checks, but the report acknowledges that the latest science cannot stop the spyware on individual computers that can change data before it gets to the election authorities.

Citing the Experience of European Countries

Although several countries considered online voting around the turn of the century, concerns about cybersecurity had a significant impact. In 2017, France backed off from its plan to let its citizens living in other countries use online voting for legislative elections. Swiss researchers found a flaw in the source code in March 2019 that had the potential to let malware change voter preferences without notice.

Some supporters of the Swiss development defended its merits by claiming that only “someone on the inside” had the ability to exploit the system. However, one of the researchers regards the prospect of an insider allowing it to happen only exacerbates the problem. She emphasized her view that no election system needs “a backdoor” that lets anyone “undetectably modify the election outcome.”

The Swiss researchers who discovered the flaw did not participate in a government contest to hack the election system, but they examined the source code that the contest allowed for release. Their findings have far-reaching implications that extend to “at least 1,400 U.S. counties” as well as 42 other countries. The software developer behind the Swiss system operates in those locations as well. The Russian influence in the 2016 elections in the United States gives the countries pause as they consider a return to the use of paper ballots that hackers cannot alter.

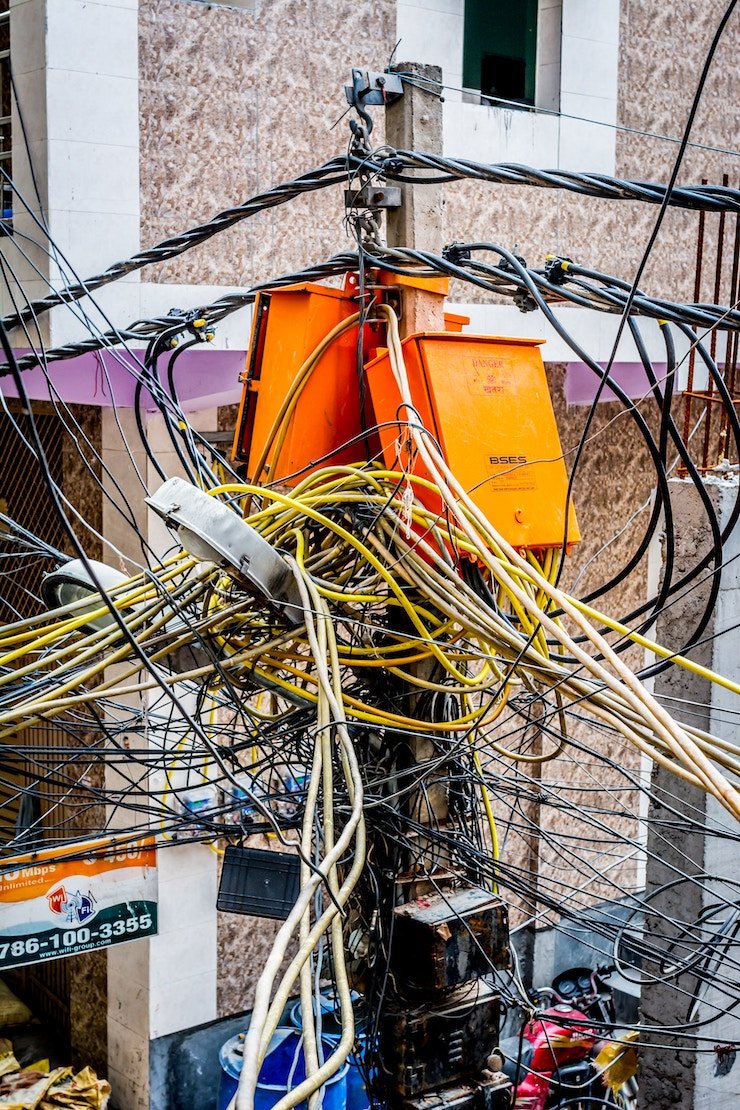

Considering the Risks of Internet Access

Lack of acceptance of the concept of internet voting involves trust issues and concerns about cybersecurity that raise threats to its viability. However, users who have concerns about internet security have access to effective countermeasures in the United States and around the world. SCANDABLE, a comprehensive software vulnerability scanner, can detect hundreds of vulnerabilities and alert an active team to keep it up to date.

While stories of hacking and internet security abound, credit for them may not belong to the skill of the hackers as much as human error. An inscription over the entrance to the National Archives in Washington, D.C. states that “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” One careless act by an employee of failing to exercise vigilance can produce dire consequences, but web users have access to some safeguards. SCANDABLE can check for vulnerabilities that may occur without notice, and its dashboards keep you informed of what it finds. When you access the web, it provides identification as you connect to your servers, and it lets you know about unnecessary services that may appear on your web application through its web security check capability. You can have defenses that protect your security on the web.

The consensus of opinion about internet voting, not including that of Estonia, seems to favor avoiding the practice. Experiments with it have shown that, while the software for voting systems becomes more complex, it also makes election fraud possible. The susceptibility of computers to hacking and security threats makes them an unreliable tool for voting. The accuracy of a voting process that allows questions of reliability to occur puts the system in jeopardy. An expert who served as Virginia’s Department of Elections deputy commissioner for four years doubts the reliability of internet voting. “No cybersecurity expert that I know of,” she said, “endorses any sort of platform” as a secure option for online voting. The insecurities in commercial voting machines make their use problematical as well.